Time to Talk on Added Sugar Policy

Late last month, the New York State Court of Appeals ruled that the New York City Board of Health exceeded the scope of its regulatory authority by adopting the “Sugary Drinks Portion Cap Rule”. The majority opinion concluded that in choosing this policy goal, the Board of Health “without any legislative delegation or guidance engaged in law-making and thus infringed upon the legislative jurisdiction of the City Council of New York.”

The New York Times called the decision “a major victory for the American soft-drink industry, which had fought the plan.” New York City Health Commissioner Mary Bassett noted that “Today’s ruling does not change the fact that sugary drink consumption is a key driver of the obesity epidemic, and we will continue to look for ways to stem the twin epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes by seeking to limit the pernicious effects of aggressive and predatory marketing of sugary drinks and unhealthy foods.”

So the strategy of reducing diet-related premature deaths and preventable illnesses by limiting portion sizes of sugary beverage appears to be off the policy table in New York for now. But the defeat of this approach to reducing sugar consumption does not change two simple truths.

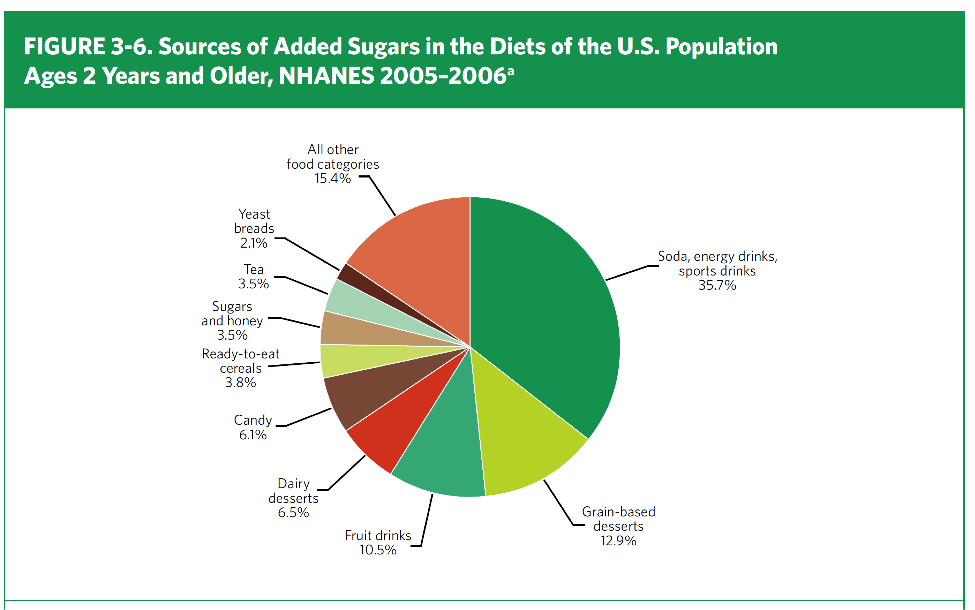

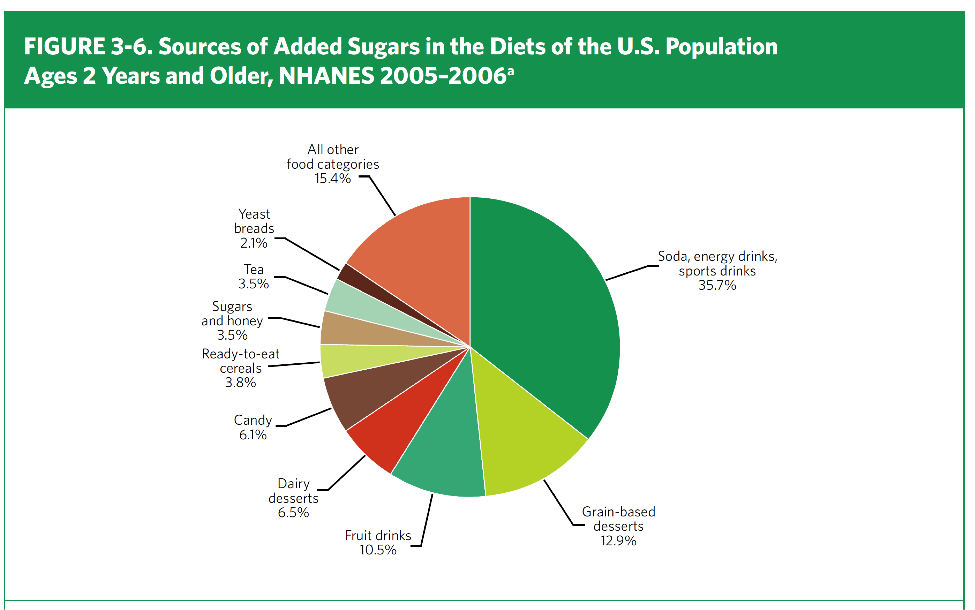

First, all Americans—from the tax payers who pick up the burden of sugar-related health care to the low-income, Black and Latino populations that experience the highest burdens of obesity and diabetes—will benefit from reduced sugar consumption. Since most sugar we consume is “added sugar” – put in our food by food manufacturers rather than Mother Nature or our own spoons, the goal of health policy has focused on reducing these added sugars.

Second, most independent scientists agree that soda and other sugary beverages have played a major role in our epidemics of diet-related disease. Like the climate deniers, Coca Cola, PepsiCo and other Big Sugar producers (and the scientists they hire) work hard to undermine this growing consensus, but most international health organizations now agree that reducing global sugar consumption should be a priority for controlling diet-related diseases, after tobacco the world’s leading preventable killer.

The defeat of NYC’s portion cap provides health professionals and the food movement with the opportunity—and the responsibility— to deliberate on what policies might be most effective and feasible in reducing sugar consumption.

Eight Approaches to Reducing Added Sugar Consumption

Fortunately, many policy tools are available for lowering sugar consumption. The defeat of New York City’s soda portion cap provides public health and nutrition professionals and the food movement with the opportunity—and the responsibility— to deliberate on what policies might be most effective and feasible in reducing sugar consumption. In the last few years, advocates have often advanced soda policies without considering the range of options or strategizing what it would take to win. To avoid repeating this mistake, I briefly describe several of the policy approaches that have been proposed, then consider the characteristics of a good sugar policy. My goal is to encourage intense discussion among health advocates on next steps for sugar policy.

Education includes policies and programs that inform people about the risks of excess sugar consumption. It is based on the premise that changing people’s understanding of sugar and disease will lead to individual decisions to reduce consumption. Nutrition education that includes information about sugar can be offered in schools, health care institutions, community centers, churches, SNAP programs and in mainstream and digital media. More sugar education can be the result of other approaches described below, e.g., regulations for mandatory labeling of added sugar. Examples of sugar-focused education include the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Pouring on the Pounds media campaign, mandated sugar labeling or sugar warning on packaged food, and counter-advertising campaigns that adapt the lessons from the truth campaign, an effective anti-tobacco campaign that appealed to rebellious youths’ resistance to being manipulated by the tobacco industry that looked to profit at their expense.

Regulation describes government rules that result in less added sugar in our food. Regulations can require:

- Food industry to reduce amount of sugar in food

- Limits on advertising unhealthy food to children

- Government agencies to set standards for amount of sugar in food they serve (e.g., USDA rules for school food, New York City Food Standards for meal programs in city agencies)

- Food makers or public agencies that serve food to limit size of portions or number of vending machines slots dedicated to sugary beverages or licensed retailers to limit portion size (e.g., defeated portion cap rule)

- Food industry to label amount of sugar in product, post calories or put warning labels on front of packages of high sugar foods.

Public Benefits such as WIC and SNAP (food stamps) could set rules that limit the use of such benefits for products with high levels of added sugar. They could also provide incentives that encourage users to purchase only lower sugar foods. Currently, significant portions of the money spent on food benefit programs ends up as profits for manufacturers of high added sugar products, a case of public subsidies for these manufacturers and retailers and thus the diet-related diseases they cause. One study found that low-income children receiving SNAP benefits consumed 43 percent more sugar-sweetened beverages than low-income children not receiving SNAP, an uncomfortable finding that warrants policy attention. One proposal calls for incentives that would offer higher benefits for healthier foods. WIC recently set new food standards that included products with reduced sugar.

Public food programs in schools, hospitals, jails, child care, afterschool and senior centers use public dollars to buy food they serve their populations. Creating procurement policies that encourage reductions in added sugar can lower sugar intake for many at risk of diet-related diseases.

A poster from Healthy CUNY’s student created Fight the Fizz Campaign.

Taxation policies allow local, state or national to tax sugar or sugary products. Among the proposals have been:

- Tax on soda (e.g., successfully implemented in 2013 in Mexico, a country with high and rising rates of obesity and diabetes, in 2013) or other high sugar products

- Excise tax on sugar to be paid by manufacturers

- Tax on High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS)

Others have suggested alternative strategies to increase prices of sugary beverages including rules that set a minimum price for an ounce of soda (an approach to alcohol control in Scotland) and prohibitions on coupons and discounting.

Lower dietary guidelines for sugar consumption can contribute to public discussions and institutional and individual choices about food. Most such guidelines recommend limits on sugar consumption, although the levels vary widely. Americans now consume an average of 16 percent of their calories from added sugar. The USDA 2010 Dietary Guidelines urge American “to reduce the intake of calories from solid fats and added sugars” but do not give a quantitative goal for added sugar. A recent draft report from the British Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition recommended that the “dietary reference value for free sugars should be set at a population average of around 5% of dietary energy for age groups from 2.0 years upwards.” The World Health Organization has also recently proposed a 5 percent limit on calories from added sugar, acknowledging that such a target is now “aspirational”.

Ending Sugar Subsidies could reduce sugar consumption by increasing the price of added sugar. Currently several government programs subsidize sugar and the promotion of sugary diets. These include agricultural subsidies for growing sugar, tax breaks for the costs of advertising high sugar foods and for Big Sugar’s lobbying expenses, and the SNAP subsidy to producers and sellers of high sugar products. In addition, other federal policies place tariffs on imported sugar in order to keep domestic prices for cane and beet sugar artificially high, a benefit to politically well-connected U.S. sugar growers –but also a contributor to higher sugar prices and presumably lower sugar consumption. Every year, the U.S. candy industry tries to end this tariff to enable them to lower the cost of producing candy. Another paradoxical consequence of this sugar tariff is that it makes HFCS a lower cost alternative sweetener for Big Food, encouraging its use.

Divesting from industries that continue to promote sugar consumption could lead some brand name companies to change their marketing practices. Corporate social responsibility campaigns forced Nestle to change its global marketing practices for infant formula, hastened the defeat of the apartheid government in South Africa and is now leading some universities to divest their holdings from coal companies. In the past, CALPERS, the nation’s largest health and pension fund that represents California state workers, has divested from tobacco and gun companies based on public health concerns. If every university and hospital decided to divest its endowment and pension funds from companies that continued to promote added sugar products to children, might that change food marketing practices?

Community Campaigns to cut sugar could enlist schools, hospitals, child care programs, universities and the other public and nonprofit institutions that serve food to millions of Americans to take a voluntary pledge to reduce the added sugar they serve by a fixed amount each year. Consumer groups could organize a similar campaign for chain restaurants, urging “buycotts” at outlets that took the pledge and boycotts of those that did not.

Lessons from Other Industries

In my book Lethal but Legal Corporations, Consumption and Protecting Public Health (Oxford University Press, 2014), I analyze the lessons that public health advocates can learn by comparing the strategies that the food and beverage, alcohol, automobile, pharmaceutical firearms and tobacco industries use to advance their business and political objectives. What guidance does such a comparison suggest for those promoting policies to reduce sugar consumption?

First, there is no magic bullet. None of these eight policy approaches can by itself reverse added sugar’s contribution to diet-related diseases. Each approach has strengths and weaknesses. But what tobacco activists taught us is that over time, multiple synergistic approaches lead to reductions in tobacco use. Sadly, it took fifty years to cut U.S. smoking rates in half, a delay that contributed to hundreds of thousands of premature deaths. By accelerating our multi-pronged efforts to reduce added-sugar, we can save more lives. Similarly, no single strategy—legislation, litigation, media advocacy, community organizing—will achieve the goal of reducing consumption of added sugar. Activists, public officials and public health professionals need to create a portfolio of strategies whose synergistic impact if greater than the sum of the parts. Like savvy investors, we should assemble portfolios that include some high risk, high impact strategies (e.g., litigation) as well as longer term, lower risk ones (e.g., public education).

Second, we need to re-frame the debate from the rights of individuals to choose whatever products they want to the right of corporations to profit at the expense of public health. Corporations have spent billions in advertising, public relations and lobbying to frame the choice as individual freedom to choose Pepsi or Coke; 8 ounces or 40 ounces; highly sugared, substitute sugared or no sugar. By doubling down on what they perceive as a winning frame, Big Sugar hopes to delay action indefinitely. When tobacco activists succeed in changing the frame from the industry-favored “right to smoke” to the more public health oriented “right to breathe clean air”, policy victories followed.

What are the frames and slogans that will catalyze a similar transformation in the fight against Big Sugar? Some I like are: Which is more important: The right of parents and individuals to protect their children against marketing associated with preventable illnesses or the right of corporations to advertise as they please? Who do you trust more to look out for your children’s well-being: public health officials or the CEOs of Pepsi and Coke? When we succeed in getting elected officials, parents associations, professional organizations, and civil rights groups debating these questions, we’ll be on the road to policy successes.

Third, to change the debate, we need to focus public attention on corporate obfuscation of science, manipulation of democracy, and deceptive marketing. In tobacco policy, the revelations that tobacco industry executives were lying to Congress and misrepresenting what they knew about the addictive and harmful effects of tobacco helped convince elected officials and the public that the industry was not a credible partner in policy debates. Two recent reports by the Union of Concerned Scientists lay out how the business and political practices of the sugar industry and its allies mislead the public, obscure science, and undermine health policy. Bringing this evidence into the policy debates on sugar can help to create a more favorable environment for better policy.

Fourth, we need to engage communities, constituencies and coalitions in creating and advocating for better sugar policy. Across the industries and anti-corporate campaigns that I examined, top-down strategies, ones that made no effort to elicit opinions from diverse constituencies, engage in respectful dialogue, or create broad-based coalitions were more likely to fail than campaigns that did listen, respect and involve. The most powerful asset that sugar reformers have is the power and desire of parents, families and communities to protect health, especially the health of children. Strategies that build this human capital are more likely to overcome the greater political and financial capital of Big Sugar and its supporters.

With “victories” like the portion cap rule, the soda industry may need some defeats

Finally, in planning next steps, we need to carefully consider what constitutes victory or defeat. The prolonged debate on portion caps forced Big Soda to spend probably tens of millions dollars to defeat these policies in New York City and much more nationally. Money spent on lobbying and campaign contributions was money not spent on marketing sugary beverages or going into company profits. And during the debate, soda consumption in NYC fell even more than in the nation as a whole, as shown below. With “victories” like this, the soda industry may need some defeats. Policy and media debates that keep the public focused on the harms of soda consumption contribute to reduced soda consumption and pressure the industry to respond to public health concerns.

Source: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

In my view, it would be wrong to conclude that the failure of the portion cap rule suggest public health advocates should seek an accommodation with Big Sugar — a solution on which industry and advocates could agree. In the short run, the appeal of such appeasement is evident. But as we have learned in tobacco, industry efforts to reach accommodation with critics are often an attempt to co-opt stronger, more effective regulations and divide and weaken public health advocates. Conversely, the more public the debate about tobacco became, the more that industry was forced to make compromises.

Characteristics of Good Sugar Policy

So here’s what a good strategy for added sugar policy should include. It should unite rather than divide potential supporters. Any single measure should be part of a comprehensive portfolio of policy approaches. Proponents should engage rather than lecture allies. Policies should focus attention on the practices of Sugar Industry and its supporters and not on the consumption patterns or choices of individuals. Its ultimate goal should be significant reductions in consumption of added sugar in order to reduce the incidence of diet-related diseases.

So together, let’s figure out how we get from where we are to where we want to be. Your summer assignment from this professor is to read some of the recent reports on sugar policy listed below. Talk with your colleagues and organizational partners about which policies can muster support now and which would be better as second steps. Anticipate Big Sugar opposition and plan how we can counter it. In the coming months, let’s see if we can find some ways that health and public health professionals, nutrition groups and the food movement can act together to prevent the premature deaths and preventable illnesses that those who profit from added sugar are imposing on our society.

Note: An earlier version of this essay appeared in Corporations and Health Watch.

Suggested Reading on Sugar Policy

Bailin D, Gretchen Goldman G, Phartiyal P. Sugar-coating Science How the Food Industry Misleads Consumers on Sugar. Union of Concerned Scientists, Cambridge, MA 2014

Bassett, M. Let’s Put a Cap on Big Soda. Huffington Post June 5, 2014.

Center for Science in the Public Interest. Selfish Giving: How the Soda Industry Uses Philanthropy to Sweeten its Profits. Washington, D.C., 2013.

Chan TF, Lin WT, Huang HL et al. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome in adolescents. Nutrients. 2014; 6(5):2088-103.

Goldman G, Carlson C, Bailin D, Fong L, Phartiyal P. Added Sugar, Subtracted Science How industry Obscures Science and Undermines Public Health Policy on Sugar. Cambridge, MA, Union of Concerned Scientists, 2014.

Fry C, Spector C, Williamson KA, Mujeeb A. Breaking Down the Chain A Guide to the Soft Drink Industry. ChangeLab Solutions andThe National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity. Newark, New Jersey, 2012.

Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013; 14(8): 606-19.

Mejia P Nixon L, Cheyne A, Dorfman L Quintero F. Two communities, two debates:News coverage of soda tax proposals in Richmond and El Monte. Issue 21 Berkeley Media Studies Group, 2014.

Pomeranz JL. Sugary beverage tax policy: lessons learned from tobacco. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e13-5.

Pomeranz JL. The Bittersweet Truth About Sugar Labeling Regulations: They Are Achievable and Overdue. Am J Public Health. 2012 ; 102(7): e14-e20.

Rudd Center. Sugary Drink Tax: It’s Going to work. Video. 2014.

Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Draft Report Carbohydrates and Health. This draft report from the United Kingdom’s top nutrition scientific group urges reduction in calories from sugar to 5%.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control. The CDC Guide to Strategies for Reducing the Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2010.

Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):516-24.

Zhen C, Brissette IF, Ruff RR. By Ounce or by Calorie: The Differential Effects of Alternative Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax Strategies. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2014; published online June 2.